DuneMark Yon compares the novel with the films

“Ways change” Quick links to sections below:-

Introduction

The novel Frank Herbert’s novel Dune was first published in 1965 in parts, as was common in those days in the pulp magazines. Analog Magazine, formerly Astounding, in two serials, the first, Dune World, from December 1963 to April 1964 and the second, The Prophet of Dune, in five parts, from January 1965 to May 1965, initially in the new bigger format with which the magazine experimented. (It didn’t last long – the magazine reverted back to the usual digest size for the April 1965 issue.) So, let’s get the plot out of the way. You can skip this bit if you know it already. There are spoilers, obviously. |

|

|

|

Plot Summary |

|

“There is no escape—we pay for the violence of our ancestors.” – Dune The story focuses on the Atreides family. Duke Leto has been given the responsibility, by Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV, of ensuring that the galactic supply of spice is maintained after years of poor Harkonnen governance. He moves to the planet from his ancestral home planet Caladan to do this. The local people on Dune/Arrakis, known as Fremen, leave a generally nomadic lifestyle in the desert and are in constant opposition with the Emperor’s mining operations, until now run by the Harkonnens. Culturally following a form of an adapted Islam, they regard the sandworms as holy and should be left alone. |

|

With Leto go his concubine Lady Jessica and his son, Paul. Jessica is an ex-member of the religious Bene Gesserit group who left the Sisterhood to be with Leto and bear him a son. This was against the wishes of the Bene Gesserit, who believe Paul could be the Kwisatz Haderach – a superhuman person created by 10,000 years of selective breeding with mental powers of controlling space and time who can bring the Bene Gesserit’s plans to term. The arrival of the Atreides on Arrakis does not go entirely well. Paul and Jessica escape a Harkonnen attack by running into the desert, where they are saved by the Fremen who take them in and look after Paul and his mother as if they are part of their group. Paul meets Chani and falls in love. Over time, the Fremen see Paul as their Messiah and agree to follow him with Stilgar, the leader of the Sietch Tabr group, Paul exacts revenge upon the Harkonnens and leads the Fremen to take back their planet from the Emperor and gain influence across the Empire. |

|

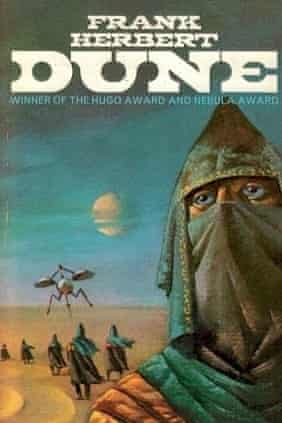

Thoughts on the serial/novel “Treachery within treachery within treachery.” Dune For those who didn’t know, the novel was nominated for the Nebula and Hugo Awards of 1965 (awarded in 1966). It won the Nebula for 'Best Novel' and tied with Roger Zelazny’s novel This Immortal [Call Me Conrad] for the Hugo, beating Heinlein’s The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, E.E. ‘Doc’ Smith’s Skylark DuQuesne and John Brunner’s The Squares of the City. In 2019 the BBC nominated Dune as one of the 100 novels that have shaped our world. Herbert himself summarised the novel in an interview as “a story of political, economic and social commentary which is carried along by a particular kind of drama, the drama of the Messiah. It originated as a study of the Messianic impulse in humankind – why do we follow the leader?” Looking back on it now, before it is turned into a fixed-up novel, it is easy to criticise the story. Herbert could be accused of merely taking his own interest in ecology and using it to create a Space Opera, albeit with similarities to our 1960s Earth. It could be suggested that melange, the spice from Arrakis traded around the Galaxy, is little more than a galactic version of crude oil. Similarly, the Guild houses were multinational conglomerates like the industrial agglomerations such as OPEC. The Fremen were similar to the nomadic desert people of the Sahara or other deserts. When talking of the plot, Jo Walton described it as “a weird cocktail, part Messianic, part intrigue, part ecological – but it works.” Whilst many on publication appreciated the Galactic-scale plot, the characterisation was fairly straightforward. The prose is rather dramatic, to say the least – Jo Walton described it as “incredibly overwritten and purple. At times it almost seems like self-parody.” when she reviewed it for Tor.com. While I partly agree, I still have a sneaking love for the prose style. And if you compare Dune World with much of what was published at the same time, it does hold up as something deeper, something denser than your typical Space Opera. |

|

Why was it so successful at the time? Well, tapping into the drug culture of 1965 and the interest in the environment couldn’t have hindered the book, in the same way that Lord of the Rings was appreciated by those attuned to nature and alternative lifestyles. The mystical element is further examined through the role of religion – both the Fremen’s worship of Shai-Hulud and the religious matriarchy of the Bene Gesserit. Psychedelic mysticism aside, Herbert does well to juggle the many elements here – the political machinations of the Emperor, the rivalry between the Atreides and the Harkonnens, the difference in culture between the Empire and the Fremen, the planet’s alien ecology itself. For me the main reason for the story’s enduring appeal are the memorable artefacts and edifices upon which the plot is constructed. |

|

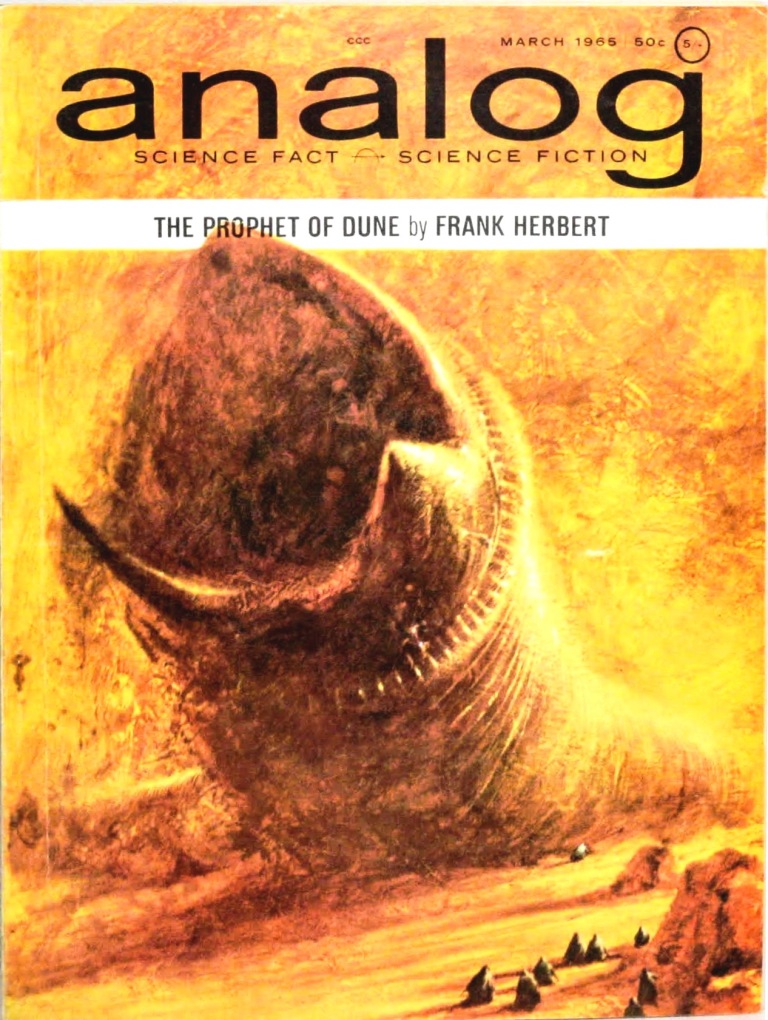

The idea of a planet made of sand is appropriately epic, as too the now-iconic sandworms, which can be over 9,000 feet (2,700 metres) long. Scientific implausibility aside, Arrakis does feel both alien and exotic, more than the usual. Most importantly, the planet itself is the most impressive thing here, something the films have tried to emulate. These remain in the memory long after the political ramifications of the Guilds have gone. It is not a coincidence that John Schoenherr’s iconic artwork for Analog magazine (approved of by Herbert himself*) have become instantly recognisable. The best example of this is the cover of Analog for March 1965, which has become so famous that it has (unsurprisingly) been available as a poster. A note on plot here. Dune World only covers the first 220 pages of the novel, The Prophet of Dune covers the next 320 pages, in the sections named “Muad’Dib” and “The Prophet”. The 2021 film only covers Dune World, the 1984 film attempts to cover the whole book.

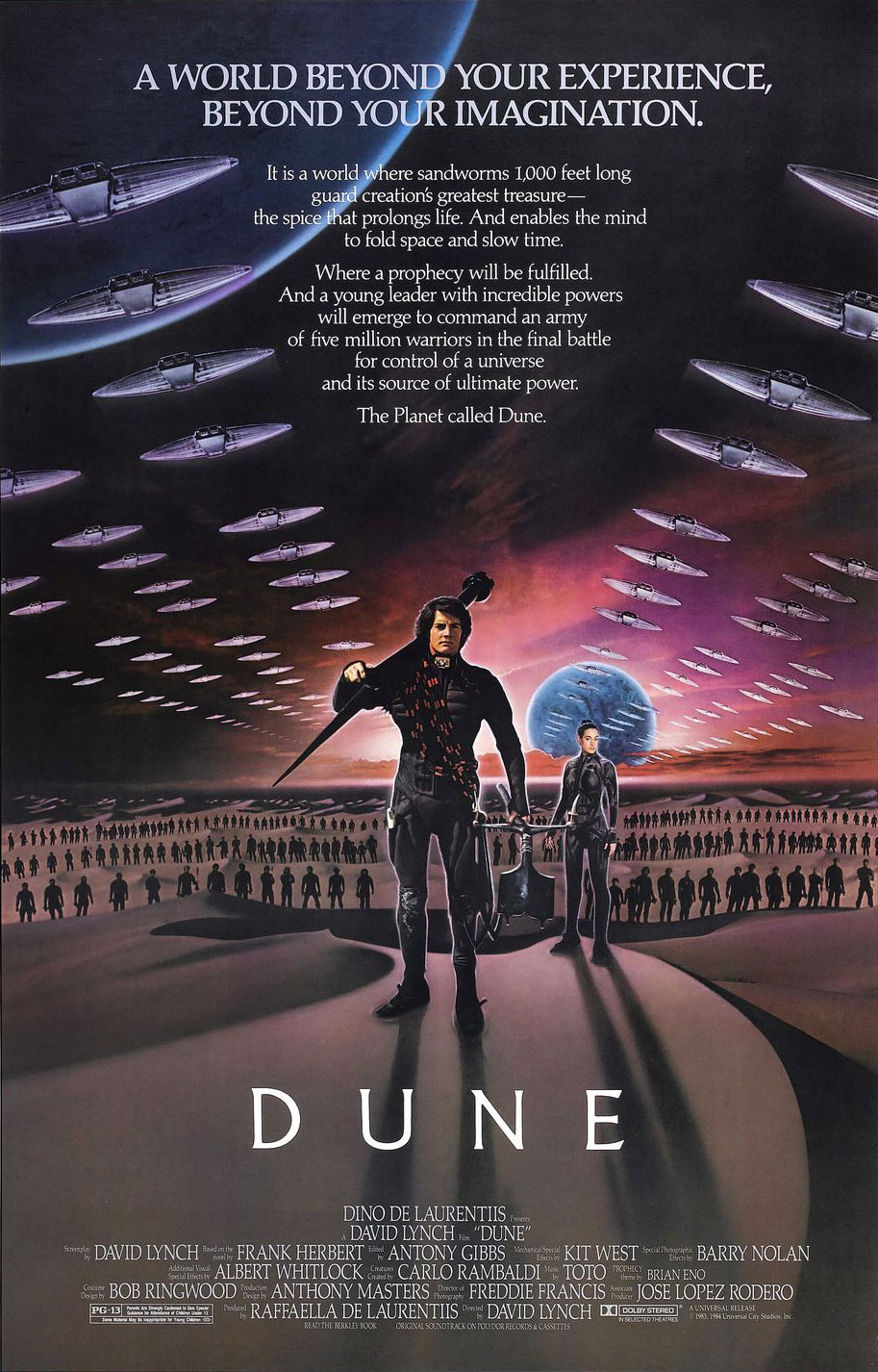

The 1984 film “Who needs to see Dune when David Lean has already made Lawrence of Arabia? It’s just King of Kings with sandworms.” – Harlan Ellison, June 1985. David Lynch’s film was an ambitious attempt to cinematically adapt the whole novel, after a number of aborted attempts by other directors.**. The stories of its production have become almost as notorious as the film itself. Delays, major edits, rushed releases – Lynch so disowned the film that he insisted that his director’s credit be taken off the film and replaced with the anonymous epithet “Alan Smithee” and his writer’s credit renamed to “Judas Booth”. The final film version was 137 minutes long. Lynch’s original cut was originally over four hours, but this was in a first cut format. The ‘long’ version was “lost”, although a longer version did appear for some television showings and a three-hour version has appeared on DVD and online. |

|

Frank Herbert himself liked the film script, stating in Starlog in January 1983 that “Believe me, it is good, about two hours, 10 minutes, maybe.”. The critics were less kind. Critic Roger Ebert’s comment is fairly typical of most. He said, “This movie is a real mess, an incomprehensible, ugly, unstructured, pointless excursion into the murkier realms of one of the most confusing screenplays of all time.” However, after entertaining us with his story of how he turned down Ridley Scott’s request for him to write a screenplay for Dune in the June 1985 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (see title quote), Harlan Ellison in the August issue was much more positive. He said, “If the adults who have viewed this film with confusion are wrong and more than fifty years of the popularity of science fiction has created an audience capable of the joys of the intellectual mind-leap, then Dune will reach and uplift its intended viewers. But if the audience has been too far debased with simplistic twaddle, then like 2001 this film will have to wait for the judgement of time.” |

|

Having watched all three versions of the 1984 film, the first time in the cinema and most recently on 4K, I must admit that I prefer the longer version in that the plot is given chance to breathe. In the shorter version Lynch has been compressed so much that there are times when the revelations become seemingly relentless, which I am sure can only have confused Dune-novices even more. This is exacerbated by the rather clunky exposition dropped in to explain to those not really following the plot what has happened. (On re-watching, I was reminded of Ridley Scott’s film Blade Runner (1982) which suffered a similar fate. In one of those moments of ironic connectivity, Blade Runner is a film for which Villeneuve has directed a sequel, Blade Runner 2049 (2017).) Whilst the pacing of the longer version is even more uneven, generally the look of the film is impressive. The opulence of the Empire being reflected in gold and glossy surfaces as if in some sort of baroque boudoir at times rivals Flash Gordon (1980) for its gaudy appearance. The special effects now seem sadly dated but were fairly impressive at the time. |

|

Paul Atreides is played admirably by Kyle MacLachlan, but is clearly more of a Luke Skywalker type character than Timothee Chalamet’s version, who to me seems a little bit more Bruce Wayne in manner. On the downside, at times the acting is a victim of excess, Kenneth McMillan’s deliberately obscene Baron Vladimir Harkonnen being a case in point. Sting as Feyd-Rautha in his underpants have become sadly iconic of the film, and is often the thing that most people remember of the film***, although for me the image of Patrick Stewart as Gurney Halleck going into battle with a gun in one hand and a pug under his other arm is another low-point. And then we have the to-be-expected moments of Lynch-ness – the way that the embryonic Guild Navigators travel between spaces is both odd and yet so typically Lynch. Some will like this, the director adding his own stamp to the film - others not. But to my mind it is OK. The film is not, despite some critics claiming it so, an unmitigated disaster. |

Sting as Feyd-Rautha. Sting as Feyd-Rautha. |

|

Generally I regard the 1984 Dune as an ambitious yet flawed attempt to bring the book to the cinema screen. It’s not perfect but there’s a lot of it that still appeals. I like it a lot, and always wonder what Lynch’s Director’s Cut version would have been like. Last note here. I know I haven’t mentioned the television series version here, mainly because I wanted to stick to the film versions. The television series has its fans and its critics. Personally, though the story is longer and therefore fuller, in my opinion the limited budget and over-preponderance of early 2000’s CGI makes it a difficult watch for me. At least they did go further – onto Dune Messiah and Children of Dune, admittedly.

The 2021 film “When Is A Gift Not A Gift?”– Baron Vladimir Harkonnen Dune film, 2021. And so to the new film directed by Denis Villeneuve. I liked it a lot, although many critics have mentioned it is lengthy and leisurely running time – 156 minutes to cover the Dune World part of the novel – less than half the whole novel. Although the story is generally the same as the novel or Lynch’s film, the way in which the tale is told is different. As each director makes his own version, understandably there are elements that are re-emphasised, whilst others are less obtrusive. Less noticeable are the machinations of the Spacing Guild, gone is Feyd-Rautha (although there are rumours that he will appear in Part Two – with his underwear less visible, I hope!) and Princess Irulan. The view of the Muslim-like cultures in the new film is more sympathetic and respectful, and the perspective of the story is more balanced. This version feels more like a proper ensemble piece than the 1984 adaptation, where ‘stars’ have their moment in the spotlight before returning to the background.

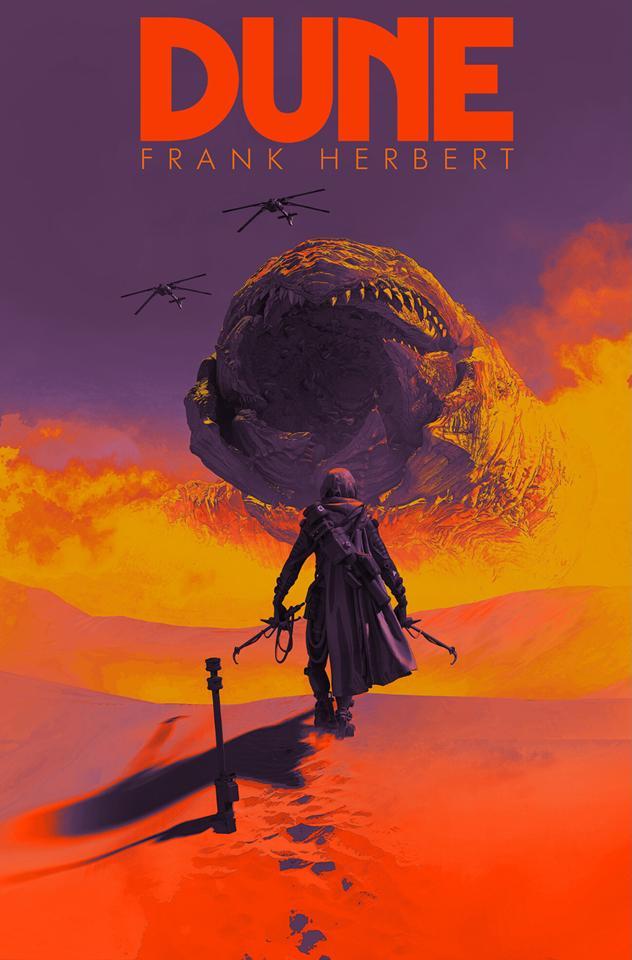

The overall look of the film is terrific – hinting at epic yet rather understated. Subtle desert landscape shades of orange and shadow emphasise the zen-like uniformity and differences of the desert landscape, whilst the science-fictional elements covering distances between planets, the spaceships, are appropriately huge and inspiring. The arrival of the Spacers Guild is exactly how I hoped it would be. Similarly, on the planet’s surface the ornithopters are wonderful, although I must admit that the sandworms, I believe based on an earlier version rather than Schoenherr’s Analog version, disappointed me a little. Nevertheless, it is a film that deserves – no, demands – to be seen on a BIG screen. I do wonder what Frank Herbert would have made of it? My only very minor niggle was the use of bagpipes in the film, which although understandable (the Atreides are a military family with a long heritage, etc) jarred a little. I couldn’t help wincing, being reminded of that ‘Amazing Grace’ moment in Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan (1982) which for me also slightly marred a great film. Nevertheless, whatever your personal view of the film is, it can’t be denied that it has got people talking about Science Fiction in films in a way that hasn’t happened for a long time – superhero films excepted. What the latest film does is take Herbert’s prose (mainly) and re-imagine it in a visual form for modern day audiences, many of whom are inured to the image rather than the written word. Villeneuve has managed to do that difficult thing of satisfying audiences old and new. Knowing a little of the background to the series, I enjoyed it as entertainment as much as the members of my family who saw it and knew very little about it. And whilst it could be pointed out that this new excitement about SF is based on a book over 55 years old – where’s the new SF being developed in film? – in my opinion this resurgence of interest in an old novel to make an intelligent yet entertaining film can only be a good thing. Whilst the source material may be flawed to contemporary eyes, the visual re-interpretation of that material for a 2021 audience means that Dune will be memorable for many for a long time to come. Part Two of the film is currently scheduled for 2023. Personally, I can’t wait. Mark Yon

* To quote: “I can envision no more perfect visual representation of my Dune world than John Schoenherr’s careful and accurate illustrations.” – Frank Herbert. ** Ridley Scott tried, then gave up. Alejandro Jodorowski was another. I recommend watching the documentary, Jodorowski’s Dune, if you get chance to see it. His version, had it come to fruition, would have been about 10 hours! *** I believe it was also available as a poster at the time of the film’s release!

[Up: Article Index | Home Page: Science Fact & Fiction Concatenation | Recent Site Additions] [Convention Reviews Index | Top Science Fiction Films | Science Fiction Books] |