|

SF Film recommendations

from the 20th Century

2: The Golden Age (1950-59)

With cinema now over a century old, present-day

genre enthusiasts can easily forget what came before

and what inspired science fiction fans of yore.

Tony Chester identifies these early offerings and

SF2 Concatenation provides links to the films' trailers.

This is the second of a series of articles that charts SF film

through the 20th century.

In case you missed it click below for the series' first article

1: Before the Golden Age (1895-1949).

This article's quick links

Introduction

A word on 'turkeys'

Allied genres and mainstream

The films

The subsequent articles in this series will follow shortly.

Obviously 'Golden Ages' are often, indeed usually, a very personal thing. The SF films of the fifties were what I was watching, growing up as a child in the sixties, as they were more or less all available on TV. But I think it is also fair to say that the fifties were a Golden Age for SF cinema, not least because of the sheer explosion of talent and material. The public had been softened up for SF content, partly by the films of the previous half century, but mostly due to the recent World War and the atomic monster it made public over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. (It is interesting that radium replaced drugs as the MacGuffin in 1955's Kiss Me Deadly, which is otherwise a routine Mickey Spillane thriller). But post-war prosperity gave way to Cold War paranoia which affected not just the content of films, but Hollywood itself when investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee – McCarthy's (and Nixon's) anti-commie bully boys, who also 'investigated' comics, on the back of Wertham's Seduction of the Innocent, and near-ruined Bill Gaines and EC Comics. So yes, there are a lot of invasion/paranoia films, and an equally huge amount of radioactive (usually giant!) lizards and critters. But I hope you will see as we poodle along that there were also a hell of a lot of really interesting films along the way. Notwithstanding that there was also a lot of crap or, to put it more politely, 'turkeys'!

A word on 'turkeys'. Some films are 'turkeys' purely because they have low production values, but I would argue that if you can discern the intent to make a good film, then you should be a little more forgiving. And, furthermore, there is a special class of 'turkey' film: those that are 'so bad they're good', and yes, that is a matter of personal taste, but I am sure you can all think of your own examples. So, while not exactly 'recommendations', I would be happy to encourage anyone to check out 'turkeys' like Robot Monster (1953), which lost the Golden Turkey Award to Edward D. Wood's Plan Nine from Outer Space (1956), or his Bride of the Monster (1956); this is the film being made in Tim Burton's 1994 release Ed Wood). You can thrill to the fun of Attack of the Crab Monsters (1956), The Deadly Mantis (1957), Invasion of the Saucermen (1958), The Brain Eaters (1958), Missile to the Moon (1958), The Giant Gila Monster (1959) and The Killer Shrews (also 1959). If you are feeling particularly masochistic, why not check out the Abbott and Costello films from the decade? Abbott and Costello met the Invisible Man in 1951, and went to Mars and met Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in 1953.

Horror was languishing somewhat in this decade, though it would fight back towards the end in preparation for its own creative explosion in the sixties. But few horror films really stand out from this decade. 1953's House of Wax was a gimmicky 3-D production, mirroring the use of the then available 3-D tech in SF films – this again provides a neat 'bracket' to the fifties, given current cinema's infatuation with 3-D. There was the superb Night of the Demon (1957), Corman's amusing A Bucket of Blood (1959), an early comedy horror, and the still effective House on Haunted Hill (1959), which is as good an example as any of a film transcending its limitations.

In 1954 mainstream cinema encountered Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai, which inspired an interest in Japanese films the same year as fans first met Godzilla (the same film also inspired Hollywood to re-imagine certain Japanese films as Westerns). 1954 was also extremely interesting for providing the animated feature adaptation of George Orwell's Animal Farm and the excellent (and available) BBC TV adaptation of 1984, written by Quatermass's Nigel Kneale and starring Peter Cushing, superior in every way to the subsequent versions (in 1956 and 1984 respectively). (See also below.) Indeed, I do not think that Kneale's contribution to bringing SF subjects to the public can be overestimated and certainly should not be overlooked. Remember, Dr.Who was a decade after the TV series of The Quatermass Experiment. It is also worth remembering that the general public in Britain was not completely ignorant of science. Fred Hoyle made many radio and TV appearances explaining science, and in 1957 The Sky At Night was first broadcast, which is still going today, despite the sad loss of Patrick Moore. Meanwhile, across the Pond in the US, on TV the United States were enjoying shows such as Captain Video (1949-'53 and 1955-'56), Tales of Tomorrow (1951-'56; this included an adaptation of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea), and Science Fiction Theater (1955-'57).

The fifties certainly had something for everyone and, consequently, there are a hell of a lot of recommendations. So, without further ado, let's crack on…

The films

Destination Moon (1950) dir. Irving Pichel. Following the 1940s, a decade in which there were almost no original SF films, Destination Moon singlehandedly kick-started the entire genre. George Pal, who had an enormous influence on SF cinema, produced the film, loosely based on Robert Heinlein's novel Rocket Ship Galileo (1947). Heinlein and German rocket scientist Hermann Oberth were scientific consultants, while celebrated illustrator Chesley Bonestell was the Moon set designer (with Ernst Fegte) and matte artist. For its time it was a very accurate portrayal of spaceflight, though the documentary style made the film a bit flat. Indeed, the only plot element that added any tension was that the ship might not have enough fuel to return home with everyone aboard (a familiar theme now, but less obvious then). Lee Zavitz's special effects deservedly won an Oscar.

Rocketship X-M (1950) dir. Kurt Neumann. An expedition to the Moon is driven off course (way off course) and lands on Mars, where the black & white film is tinted red. There the astronauts (Lloyd Bridges, Osa Massen, John Emery, Noah Beery jr. and Hugh O'Brien) discover the remains of a civilization destroyed by nuclear war. They are attacked by the blind mutant cavemen survivors who kill Emery and Beery and wound O'Brien. Bridges and Massen make it back to the ship with O'Brien and they return to Earth, only to run out of fuel and crash. All of which sounds a bit depressing, but it was quite brave of the film to depict not failure, but the willingness to carry on in spite of failure. Some footage from this film was 'borrowed' for Sam Newfield's 1951 film Lost Continent, which featured dinosaurs on a green-tinted planet!

The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) dir. Robert Wise. This classic of post-war SF is based on a short story by Harry Bates, 'Farewell to the Master' (1940). A spaceship lands on Earth and from it emerge Klaatu (Michael Rennie) and his 8-foot robot, Gort (Lock Martin). Shot at by the military he escapes a hospital and seeks refuge in a boarding-house where he meets a woman and her son (Patricia Neal and Billy Gray). He seeks out a scientist (Sam Jaffe) to assemble intellectuals in order that they may hear his message: Humans are to stop their aggressive ways or face destruction. Shot again, and this time 'killed', Neal must stop Gort from destroying the planet with the now immortal phrase, 'Klaatu barada nikto!' The film is less clear than the short story that it is Gort who is the senior member of the alien crew, but this is a tiny quibble for an otherwise superb film. This was re-made in 2008, starring Keanu Reeves, and it is a pretty good version despite some US-style schmaltziness toward the end.

The Man from Planet X (1951) dir. Edgar G Ulmer. A scientist (Raymond Bond) tells a newspaper reporter (Robert Clarke) that a new planet is entering Earth space. But when a spaceship lands in Scotland it is not to spearhead an invasion; instead the alien aboard is looking for help for his freezing planet. An evil scientist (William Schallert), who is Clarke's rival in love for Margaret Field, captures the alien and tortures him for information. Eventually the alien and his ship are bombarded by bazooka fire and the aliens are condemned to extinction by a humanity that refuses to help them. This depiction of a cold, unfeeling, almost villainous humanity, compared to a pathetic beggar of an alien most definitely goes against the grain of most films of the 50s and, as such, is to be cherished.

The Thing from Another World (1951) dir. Christian Nyby. Based on the short story 'Who Goes There?' (1938) by John W. Campbell (as Don A. Stuart). The film was, in fact, also directed by Howard Hawks – Nyby's credit was a 'favour'. In it a spaceship is found under the ice of Antarctica and nearby is an embedded frozen humanoid figure. Scientists (led by Robert Cornthwaite) and military personnel (led by Kenneth Tobey) dig it out and take it back to base. There it is accidentally thawed out and 'the thing' (James Arness) proves deadly, needing blood to survive and procreate. As the threat increases tensions between the scientists and soldiers force Tobey to take control. Eventually they lure the thing onto an electrified grid and zap it to death. At the time fans hated it, having hoped in the wake of Destination Moon that SF might become 'respectable' (in cinematic terms, at least) and fearing that instead SF 'monster films' would dominate the silver screen. In one sense they were right, monsters and invasions were rife in the 50s, but they were also wrong – chances are the monster cycle would have happened anyway, and it would be years before SF became respectable (if it ever did, and if that is assuming 'genre respectability' even worth bothering to want in the first place) – the film is in fact excellent, with the monster played down and barely on screen. It is the characters, and their reactions to the situation that steal the show. The other criticism was that the film betrayed the source (story) by substituting a monster for Campbell's shape-shifting creature. That was set to rights in the John Carpenter re-make in 1982 (see Part Five). This film has long since been accepted as a gem of cinematic SF.

When Worlds Collide (1951) dir. Rudolph Mate. Based on the 1933 novel by Philip Wylie and Edwin Balmer. Two worlds enter the solar system; the passage of one, Bellus, will cause tidal waves and earthquakes so cataclysmic as to wipe out humanity even before the two planets collide; the second new planet, Zyra, is habitable and will provide a new home for a handful of survivors (including millionaire John Hoyt and lovers Richard Derr and Barbara Rush) building a space ark. The scenes of Earth's devastation are mainly stock footage with some judiciously placed new shots, for instance of ships floating between the buildings of New York. The space and planet shots are mainly the work of Chesley Bonestell, who had worked on the earlier George Pal production Destination Moon. The spaceship takes off from a huge rail that runs up the side of a mountain. Lovely stuff. Gordon Jennings picked up an Oscar for Special Effects, a feat he was to repeat two years later with Pal's War of the Worlds.

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) dir. Eugene Lourie. Beating Godzilla (Gojira) by one year this can justifiably claim to be the first 'giant lizard awakened by a nuclear blast' film, though where Godzilla featured a man-in-a-rubber-suit, here we have stop motion animation, courtesy of Ray Harryhausen, following his apprenticeship with King Kong's Willis O'Brien. Based on Ray Bradbury's 1951 tale 'The Fog Horn' the film's plot would become very familiar over time: giant dinosaur comes to the big city (in this case New York) and is killed (or, in some cases, is not). The beast in this instance also carries plague germs, but is still eventually lured into an amusement park where it is despatched. Grossing 25 times what it cost (US$5million compared to the US$200,000 it cost to make) Beast set a box office trend that many tried to follow.

Donovan's Brain (1953) dir. Felix Feist. This is the best of three films based on Curt Siodmak's 1943 novel (the other two being The Lady and the Monster (1944) and Vengeance (1962)). Dr. Cory (Lew Ayers) tries to save the life of megalomaniac tycoon Donovan (Michael Colgan) but only succeeds in saving his brain. It develops the ability to possess Cory and tries to kill his assistant (Gene Evans) and wife (Nancy Davis, later Reagan). There have been many takes on this idea, including the 1965 Outer Limits episode “The Brain of Colonel Barham” directed by Charles Haas.

Invaders from Mars (1953) dir. William Cameron Menzies. This was the last film directed by Menzies (director of Things to Come) and the first 'invasion' film to be shot in colour. Using the trick of child-height camera work for the most part (later used by Spielberg for ET), it tells the story of a kid (Jimmy Hunt) who witnesses the landing of a UFO. When his parents (Leif Erickson and Hillary Brooke) investigate they return changed and unemotional. A doctor (Helena Carter) and an astronomer (Arthur Franz), though sceptical, check things out and discover the truth. They are captured by tall, bug-eyed green aliens (looking a little silly in velvet suits) and taken before the leader (Luce Potter, a midget actress), who is little more than a tentacled head in a round glass tank. They are rescued by a colonel (Morris Ankrum) and the invaders destroyed. The US version has Hunt waking up to find it was all a dream, only to hear a saucer land, but the European version cut this and substituted extra footage elsewhere (and, consequently, runs four minutes longer, 82 as opposed to 78minutes). This nightmarish little chiller is for kids, but does not condescend to them, and is still full of the 50s communist paranoia of the time – perhaps the parents have become reds! This was re-made in 1986 by Tobe Hooper.

It Came from Outer Space (1953) dir. Jack Arnold. This film has a number of 'firsts' – it was Jack Arnold's first foray into SF, was the first to be shot for a 3-D release, was the first to use desert locations, and the first to have aliens 'replacing' humans. Based on a screen treatment, 'The Meteor' by Ray Bradbury, it has Richard Carlson as an astronomer who witnesses an alien landing. The mostly invisible, but eventually seen as cyclopean, aliens need to make repairs to their ship, to which end they replace humans with doubles so as to use them as mechanics. Carlson defends them once the townspeople realise what's going on and attack, and the aliens eventually fly off with no one the worse for wear. A very poor remake/sequel was made for TV in 1996, It Came from Outer Space II directed by Roger Duchowny.

The Twonky (1953) dir. Arch Oboler. Based on the 1942 short story by Henry Kuttner (as Lewis Padgett). A philosophy professor (Hans Conried) is given a TV set by his wife (Janet Warren) which becomes animated. At first it is relatively helpful, performing household tasks by means of an electronic beam, but it soon becomes dictatorial and hypnotizes anyone who opposes it. Eventually the professor wakens to his situation and destroys the machine. Radio producer Oboler hated TV (as did much of Hollywood), but this film was so bad even United Artists gave it only a grudging release and that after shelving it for 17 months. This is, at best, a curiosity with many people preferring Oboler's 1951 offering about the last five people alive, Five. I can't say I agree.

War of the Worlds (1953) dir. Byron Haskin. Based on H. G. Wells' The War of the Worlds (1898). The story is by now familiar enough: Martians invade the Earth and their deadly machines prove unstoppable (even by a nuclear bomb). When nothing can stand against them they start to fall, the Martians within succumbing to Earthly bacteria. Though the film updates Wells' story from late-19th century England to mid-20th century America, and takes other liberties besides, it has to be said that the film remains true to the book. The replacement of Wells' tripods with sleek manta ray-like flying saucers can be forgiven, both because the craft are beautiful in themselves, but also because beneath them one can see three lines of force holding them aloft. If anything is weak about this film it is the lacklustre romance between its stars Gene Barry and Ann Robinson and, perhaps, the invocation of God as the true saviour (since 'He' made the bacteria), which would not have sat well with Wells and rather ignores the fact that, presumably, 'He' made the Martians as well. Despite frequently seen wires, the special effects over all are very good and won an Oscar for Gordon Jenning, which he could add to the one he had won two years earlier for When Worlds Collide. Spielberg re-made this in 2005 starring Tom Cruise. This re-make had, as would be expected early in the 21st century, good special effects, but was spoiled by changing the story to having the Martian machines buried underground for thousands of years for some contrived reason.

The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) dir. Jack Arnold. Following the discovery of the fossil of a webbed hand Richard Denning, Richard Carlson and Julia Adams mount an expedition to the upper Amazon where they are stalked by an aquatic humanoid, implied to pre-date humans. Adams is the creature's main interest; Denning wants to kill it, Carlson to capture it. The underwater sequences are stunning, Ricou Browning playing the creature, though on dry land it was Ben Chapman in the best rubber suit ever made. This film and its first sequel, Revenge of the Creature (1955), were both shot in 3-D, though the second film is rarely seen in this format. Arnold directs again and Browning returns as the creature, this time captured and taken to Florida where Lori Nelson catches his eye. John Agar and John Bromfield are the icthyologists who try to teach the creature to speak. The second sequel, The Creature Walks Among Us (1956), was directed by John Sherwood and the creature was played by Browning and Don Megowan. Jeff Morrow and Rex Reason are the scientists who capture the creature after its gills are burnt off, who try to mutate its blood and make money from the space programme. This last effort is missable.

Devil Girl from Mars (1954) dir. David MacDonald. Definitely a British cult classic, though many critics unnecessarily hate this film. Nyah (Patricia Laffan) arrives from Mars in a flying saucer with her death-ray wielding robot Chani and isolates the Bonnie Prince Charlie Inn in the Scottish Highlands. She looks great in her black leather outfit, has a paralyser ray, can blur into the 4th dimension, and is looking for healthy men to repopulate her planet (she kills a helpless cripple as 'a hopeless specimen'). A young Adrienne Corri (later to appear in A Clockwork Orange) works behind the bar; Peter Reynolds, her boyfriend, is an escaped killer; Hazel Court is an unhappy model; Hugh McDermott a newspaperman; and Joseph Tomelty a scientist. Well worth seeing.

Godzilla (1954) dir. Inoshiro Honda. The first of the Godzilla films, or rather Gojira, is the film that started the whole 'monster cycle' of Japanese films, and the repercussions continue to this day. One year after The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms Toho Studios created the original man-in-a-rubber-suit film. The plot is familiar: Godzilla is revived by a nuclear blast and stomps Tokyo flat but is defeated, after all human weapons have failed, by a scientist who has found a way to remove oxygen from water. The US version (1956) substituted footage with some American actors featured, notably Raymond Burr, and runs some 16 minutes shorter than the original (81minutes compared to 97minutes). Thankfully these days the original film has been fully digitally restored and Gojira can be seen in all its evil glory. Godzilla appeared in at least 16 films over 20 years, metamorphosing from a bad guy into a good guy in the mid-sixties, and led to the creation of Rodan, Baran and Mothra, fought King Kong and Mecha-Godzilla, and inspired other studios, notably Daiei, to create their own monsters, for example Gamera and Gappa. 10 years after production on these films ceased Godzilla was briefly revived for Godzilla 1985 (1985) dir. Kohji Hashimoto, but it flopped and that was it until the Roland Emmerich/Dean Devlin 1998 re-make.

Them! (1954) dir. Gordon Douglas. Near atomic testing grounds two cops (James Whitmore and Chris Drake) find a terrified little girl (Sandy Descher), a destroyed trailer-home, and a pile of sugar. Dr.Medford (Edmund Gwenn) and his daughter Patricia (Joan Weldon) join forces with an FBI agent (James Arness) to battle mutated giant ants. They kill the ones in the desert, but a queen escapes and lays her eggs in the storm drains of Los Angeles where a final confrontation takes place. This film spawned several imitations such as Tarantula, The Deadly Mantis (1957) and The Black Scorpion (1959). The ants were giant mock-ups, not photo-enlarged real ones.

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) dir. Richard Fleischer. This is a Disney production and probably the one that is best remembered today. James Mason is Nemo who uses his submarine the Nautilus to destroy ships carrying munitions. He picks up three shipwrecked men, Kirk Douglas (an awful hammy performance) as a harpoonist, Paul Lukas as a scientist, and Peter Lorre as his valet. Various attempts to escape form the bulk of the plot, but it is the Oscar-winning special effects of Ub Iwerks that are remembered, especially the fight with the giant octopus (John Meehan and Emile Kuri also picked up an Oscar for Art Direction). The underplayed anti-war message is symbolically re-iterated at the film's climax when the atomic sub explodes producing a mushroom cloud. Over all this is not very satisfying; bad as Douglas was, Mason was not far behind, coming across as a vengeance-fuelled madman rather than having any philosophical integrity. Then again, this is really a kids' film, so what would they care?

Conquest of Space (1955) dir. Byron Haskin. The producer, George Pal, and director had successfully collaborated on the 1953 classic War of the Worlds, though Pal saw this as more of a sequel to his 1950 film Destination Moon. Based in part on Werner von Braun's 1952 part academic and part popular science book The Mars Project (first English edition 1953) and also on The Conquest of Space (1949) by Chesley Bonestell and Willy Ley, the 1955 film was interfered with by the studio (Paramount) until all that remains is a dodgy trip to Mars, with a script that had picked up some scientific impossibilities (such as an asteroid burning in vacuum!). The commander of the expedition (Walter Brooke) turns into a religious maniac and tries to sabotage the mission, only to be stopped, and killed, by his son (Eric Fleming). Bonestell's matte paintings are the highlight of the film, though the mattes and effects are clumsily executed and, though fondly remembered, the film is something of a flop worth seeing mainly for nostalgia's sake.

It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955) dir. Robert Gordon. The 'it' in this case is a giant irradiated octopus that attacks San Francisco. This film features an early example of Ray Harryhausen's stop-motion animation, and very good it is too. Due to budget restrictions the octopus only has six tentacles, instead of the customary eight, but that doesn't matter as it convincingly drags a ship into the depths, severs the span of the Golden Gate Bridge and even crawls about on land before finally being killed by an atomic torpedo. Donald Curtis and Faith Domergue are the helpful scientists and Kenneth Tobey the plucky submarine captain charged with stopping the monster.

The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and Quatermass II (1957) both dir. Val Guest. The first film is an adaptation of the 1953 BBC TV serial that starred Reginald Tate as Quatermass and Duncan Lamont as Victor Caroon. The film substituted Brian Donlevy as Quatermass and Richard Wordsworth as Caroon. The professor sends a rocket into space but, when it returns, two of the three astronauts who left are missing. Caroon has been infected by alien spores that cause him to mutate into an amorphous creature that absorbs living material (beating The Blob by a few years). Eventually it is electrocuted in Westminster Abbey. This film has the dubious distinction of actually having frightened one of its audience to death! In 1956 in Oak Park, Illinois, a small boy's heart collapsed during a screening (apparently when the rocket exploded), according to the coroner. The second film, also with Donlevy, adapts the 1955 serial which had starred John Robinson. Small objects rain down onto the Earth from space; these carry small aliens which can possess a human. Those infected then set up a huge plant to house further creatures, feed them and, it is implied, to begin a sort of reverse terraforming operation to convert our atmosphere to be more like theirs. Quatermass rouses the workers from the nearby town to what's going on and they storm the plant. The ending to the TV serial, in which Robinson goes to the asteroid base of the aliens and destroys it, is dropped from the film. This was about the same time as Invasion of the Body Snatchers and has similarities to it. A third film followed much later than the 1958-9 BBC serial on which it is based. On television Andre Morell was Quatermass; in the Quatermass and the Pit (1967) it is Andrew Kier. What is thought to be an unexploded bomb is found in London, but it turns out to be an ancient spaceship. From evidence in the pit Quatermass is able to deduce that insectoid aliens experimented on mankind's ancestors. One of the consequences is that we have picked up their drive for a culling of 'mutants' from the population and, influenced by the release of the craft's energies, half of the capital's people turn on the other half. The alien force is eventually 'short-circuited' and grounded. The first of these films is also known as The Creeping Unknown, the second as Enemy from Space, and the third as Five Million Years to Earth. There was a fourth Quatermass TV series in 1979, starring John Mills, which concerned the 'harvesting' of humans by aliens, and this was edited down into a film. Both series and film were known simply as Quatermass, though it was also known as Quatermass the Conclusion. The series was poor, the film version poorer still. The original films, however, are uniformly good (if not quite as good as the series on which they are based) and show British SF in a good light. Furthermore it was the first two films that saved Hammer from going out of business and set them on the path to their SF and horror adaptations, completely changing the company's fortunes. The second and third TV series are available on DVD, along with what remains of the footage from the first serial, all written by Nigel Kneale.

Tarantula (1955) dir. Jack Arnold. In 1954 it was giant ants in Them! (see above) that threatened lives; now it was the turn of the spider. Leo G. Carroll is looking to cure world hunger by inducing gigantism in food animals, but his initial experiment with a tarantula goes wrong when it escapes. The same formula causes acromegaly in humans, and this does for Carroll later in the film – the giant spiders in Spiders (2000) forty-five years later would have venom that performs similarly. John Agar and Mara Corday have a romance while the tarantula gets bigger and bigger, feeding on cattle and crushing cars. Finally the air force are called in (with Clint Eastwood in a bit part as a pilot) and they drop napalm on the pesky arachnid. This film was almost totally ripped off in the highly amusing Earth vs. the Spider (1958) directed by Bert I. Gordon.

This Island Earth (1955) dir. Joseph Newman. Based on the 1952 novel by Raymond F. Jones. Scientist Cal Meacham (Rex Reason) passes an IQ test by building an 'Interocitor' and is then recruited by Exeter (Jeff Morrow) to join a group of other scientists, including an old flame (Faith Domergue), to conduct pure research. However, the scientists have their doubts, which are confirmed when they discover that Exeter and his colleagues are aliens. Reason and Domergue are kidnapped and taken to the planet Metaluna (these sequences were directed by Jack Arnold) which is at war with the Zahgons. But they are too late, the Metalunans' planetary shield is fading and the meteoric bombardment of the Zahgons is getting through. Exeter is injured by a mutant when he helps the scientists escape, takes them back to Earth, then crashes his ship into the ocean. This, like Forbidden Planet, is in my opinion one of the best SF films from the mid-50s.

Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956) dir. Fred F Sears. Initially non-hostile aliens from a dying world are fired upon at a US base and, therefore, declare war on Earth. Just when it seems they'll win, scientist Hugh Marlowe, in between wooing Joan Taylor, discovers the aliens are vulnerable to high-frequency sound. Which is all the cue you need for the final battle, featuring Ray Harryhausen's excellent stop-motion animation, with flying saucers dropping onto and into Washington monuments right, left and centre. Great stuff.

Forbidden Planet (1956) dir. Fred McLeod Wilcox. A genuine masterpiece, a loose updating of Shakespeare's The Tempest, and a forerunner of Star Trek. In 2200AD an Earth spaceship visits Altair IV, with whose colonists contact has been lost. The captain (Leslie Neilson), doctor (Warren Stevens) and first officer discover Professor Morbius (Walter Pidgeon as Prospero), his daughter Altaira (Anne Francis as Miranda) and their robot, Robbie (Ariel). The other colonists are all dead, killed by an invisible entity which now threatens the ship. Morbius has discovered beneath the planet's surface the abandoned laboratories of an extinct race, the Krel, seemingly also killed by the same entity. This “monster of the Id” (Caliban) has been unleashed by Morbius' unconscious mind. The ship rescues Altaira and Robbie, but Morbius is doomed when the planet is destroyed. Robbie went on to star in The Invisible Boy (1957), and a further version of him was part of the crew in the TV series Lost In Space and appeared in an episode of detective show Colombo (and has cameos in many more series and films besides) – easily one of the most enduring robot characters of all time.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) dir. Don Siegel. Based on the novel The Body Snatchers (1955) by Jack Finney. In many ways this is probably one of the best known, and most talked about, films of the 50s. The situation is familiar: Alien 'pods' arrive on Earth, each capable of growing a duplicate of a human. When the human to be copied sleeps near a pod, memories are transferred from the 'original' who then dies and the emotionless duplicate takes their place. The action takes place in the fictional town of Santa Mira in California. The town doctor, Miles (Kevin McCarthy), and his girlfriend Becky (Dana Wynter) are the ones who find out what's going on and have to resist going to sleep. The film originally ended with Miles rushing into traffic to raise the alarm, but the drivers ignore him. However, a 'prologue' and 'epilogue' were tacked on, framing the narrative as a tale told by Miles in a hospital, so that he could finally be believed by the authorities and the day saved. The reason for mentioning it is that the 1978 remake opens with a cameo by McCarthy, recreating the scene, yelling, “They're here,” and “You're next!” There is also a cameo from Don Siegel (see Part Four). Apparently the fifties version is now available without the framing device, but I've never seen a copy. Abel Ferrara's 1992 remake, Body Snatchers, transfers the action to an army base and is told from the perspective of an 'army brat' (Gabrielle Anwar). Curiously, given Ferrara's track record, this is the most conventional of takes on the 'invasion film', with gun battles and explosions and good old human aggression (linked to emotion) saving the day. Whatever the rights and wrongs, the influence of the original cannot be over-estimated and clearly stretches all the way up to 1998's The Faculty (see Part Six).

It Conquered the World (1956) dir. Roger Corman. Lee van Cleef plays a scientist in contact with a Venusian he believes to be a superior intelligence who will help him bring 'order' to Earth. The fanged, cone-shaped monster is brought to Earth and produces bat-like creatures which implant controlling devices into humans. Peter Graves is a former friend, also a scientist, who knows fascism when he sees it and so resists. In the end it is van Cleef who burns the monster, dying himself in the process. Though this sounds slight, and the monster is undoubtedly stupid due to Corman's legendary low budgets, this is actually a very good film, with its discussions of the benefits and perils of science. This is a less black-and-white stance than in other films of the time where scientists are either 'mad' and bring about all manner of nastiness, or the 'good' willing tools of the military coming up with solutions. Last time I checked the internet, this film was costing £35!

1984 (1956) dir. Michael Anderson. Based on the 1949 novel by George Orwell. The definitive adaptation of 1984 was in fact a BBC television play (1954), adapted by Nigel Kneale and starring Peter Cushing as Winston Smith. The 1956 film adaptation is a terribly lacklustre affair, with Orwell's savage satire on the State reduced to a melodramatic romance. Winston Smith (Edmond O'Brien) rebels against his repressive conditioning in Oceania, controlled by the ubiquitous Big Brother, and follows an illicit love affair with a girl (Jan Sterling). He comes to the state's attention, betrayed by Michael Redgrave, and is tortured. The ending of the US release of the film follows the book and has O'Brien and Sterling successfully brainwashed; conversely in the British release they defy the state and are killed in a hail of bullets. The much later version, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984), makes exactly the same mistake, playing up the doomed romance and playing down the satirical content. John Hurt and Suzanna Hamilton take the parts of the lovers, and Richard Burton is the torturer (in his last screen role). In addition, the soundtrack, which is fine as a bunch of songs, is completely wrong for the film. Neither film was particularly successful.

Not of This Earth (1956) dir. Roger Corman. Paul Birch is the alien from Davana collecting blood for shipment back home. Gaunt and fragile, behind his dark glasses are pupil-less eyes whose gaze can kill. He is aided by a bat-monster, but eventually dies when a high-pitched siren causes him such pain that he crashes the car he is driving. This was quite a serious film at the time, despite well-observed and sparingly-used comedic touches, but the 1988 remake is more a spoof, despite being quite faithful to the original. Partly this was because of the fact that times had changed and so had the audiences, and partly it was because of the number of 'scream queens' and ex-porn stars thrown in for titillation. It was even re-made again, this time for TV, in 1995. A strange legacy for such a cheap Corman quicky.

X the Unknown (1956) dir. Leslie Norman and Joseph Walton. From a crack in the Earth an oozing monster emerges which feeds on radiation. A scientist (Dean Jagger) and an investigator (Leo McKern) from the Atomic Energy Commission track the creature to its underground lair and destroy it with 'electronic waves'. This was Jimmy Sangster's first script for Hammer, and something of a cash-in on their then recent success with The Quatermass Xperiment (see above), but the atmosphere is well established, the script clear, the acting better than average and the direction sound, considering that Norman had to take over from Walton when the latter grew ill in the middle of shooting. This compares favourably with the first two Quatermass films.

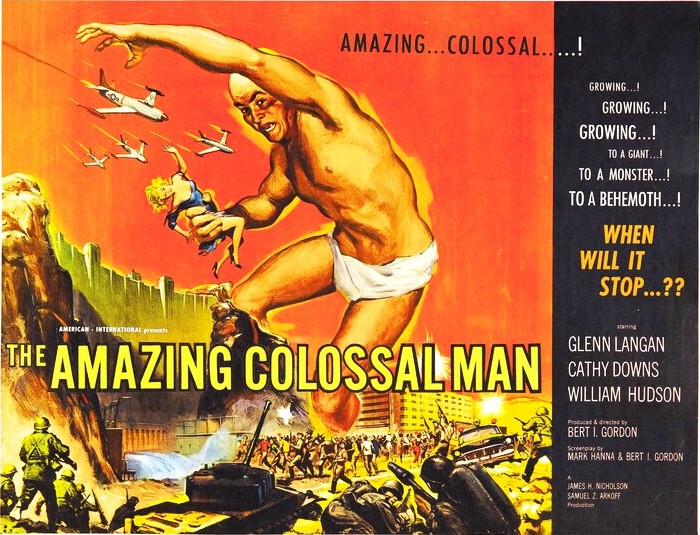

The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) dir. Bert I. Gordon. An army officer (Glenn Langan) is caught in the blast of a 'plutonium bomb' and grows to be 60 feet tall. As his relationship with his fiancée (Cathy Downs) falls apart and the transformation places him under tremendous physical and mental strain, he goes insane and begins a rampage that ends with his death at Hoover Dam. A sequel, and virtual remake, War of the Colossal Beast, followed in 1958. Gordon, an exploitation filmmaker if ever there was one, produced great posters and publicity material, but seldom (if ever) delivered with the films themselves. Nonetheless some of his work has a naïve charm and can be highly amusing, if unintentionally.

The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) dir. Terence Fisher. This was first of the Hammer films. Where Universal had concentrated their tales around the creation, Hammer concentrated on the creator, nearly always played by Peter Cushing. This continuity was helped by the fact that Terence Fisher directed five of the seven films they produced, for the most part very well. Hammer's gothic films, with the consistency of sets created at Bray and a bunch of actors that were practically a repertory company, certainly depended on horror but, by concentrating on the scientist, Frankenstein, leaned more in the direction of SF than did the Universal films. Cushing especially was very good in the role, playing it somewhat ambiguously. By turns one could see him as a dedicated man of science, committed to the preservation and creation of life, but also as a ruthless and demented man full of hubris. Christopher Lee plays the creature in the first film, ultimately falling into a vat of acid. A year later director Fisher and writer Jimmy Sangster were re-united on The Revenge of Frankenstein. The scientist escapes the guillotine with the help of Michael Gwynn's cripple, to whom he promises a new body. Frankenstein is seen as the victim of superstitious prejudice and he fulfils his promise, only to be 'killed' and his own brain transplanted to a new body. href="http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NLPsFMW84eE" target=_blank>The Evil of Frankenstein (1964) dir. Freddie Francis is best skipped over, but Frankenstein Created Woman (1967), with Fisher back at the helm, is more interesting. Robert Morris is killed and his 'soul' placed in the body of Susan Denberg (formerly his lover) who then sets about revenging her/himself on those responsible for his death. Perhaps the best of the Hammer films is Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969), with an intelligent Bert Batt script, great direction from Fisher and wonderful performances from Cushing and Freddie Jones. Effectively just a brain transplant story, rather than a full-on creature, it has a sympathetic Jones being rejected by his wife (Maxine Audley) and attacking Cushing. The Horror of Frankenstein (1970) was written and directed, poorly, by Jimmy Sangster, and Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974), despite having Fisher back again, was an indication that Hammer was losing its touch. By contrast around this time there were two Frankenstein films of note: Flesh for Frankenstein (1973), directed by Paul Morrissey, and Frankenstein the True Story 1973, directed by Jack Smight (see Part Four).

Fiend Without a Face (1958) dir. Arthur Crabtree. Based on the novel The Thought-Monster (1930) by Amelia Reynolds Long. On a US base in Canada a scientist (Kyanston Reeves) invents a machine that turns thoughts into invisible creatures of energy. These start sucking people's brains out through holes in the backs of their necks. An investigator (Marshall Thompson) is called in, but he and others are driven into, and trapped in a house. As the creatures become visible they are revealed to be brains with spinal cords attached and twitching antennae. This might all sound a bit silly, but actually this is a very atmospheric little shocker and the stop-motion animated monsters are genuinely disturbing. A great chiller worth seeing.

The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) dir. Jack Arnold. With a script by Richard Matheson based on his novel The Shrinking Man (1956). Grant Williams is caught in a radioactive cloud at sea and starts to shrink one inch per day. His life starts to fall apart when it becomes clear that no cure will be found, and even his wife (Randy Stuart) begins to patronize him. Even his brief tryst with a midget woman is comfortless when he shrinks below her height. Chased out of a doll's house by his own cat, he ends up in the cellar, there to do battle with a spider for the few crumbs of food to be found there. Eventually, in a strangely joyful ending, it is implied that he will shrink into a new sub-atomic universe, perhaps to find new life there. The effects, giant props, rear-projection, split-screen and all are superbly done. A real classic of the 1950s SF boom. The Incredible Shrinking Woman (1981) is a partial re-make, poor and to be avoided.

20 Million Miles to Earth (1957) dir. Nathan Juran. This film was the first solo outing for Ray Harryhausen's stop-motion special effects, but has little else to recommend it. An expedition to Venus returns to Earth, crashing into the sea. A specimen of Venusian life finds its way into the care of a zoologist (Frank Puglia), while the expedition's sole survivor (William Hopper) searches for it. In Earth's atmosphere the lizard-like humanoid grows to enormous size, escapes into Rome, batters an elephant to death, and is finally destroyed atop the Coliseum. The Ymir creature is convincing (for its day) but, sadly, none of the real life actors are. A curio.

Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958) dir. Nathan Juran (here called Hertz). Superior to 1957's The Amazing Colossal Man (not difficult, some would say, see above), this film is a cult classic to some and trash to others. The unfortunate victim of gigantism in this case is actress Allison Hayes, transformed by a bald alien giant while driving through the desert. Driven wild by a cheating husband, the inevitable rampage ensues until the usual tragic consequences roll around. The claim that this is an early blow of feminism is an unnecessary justification for enjoying this offering – the laughs engendered by the giant rubber hand are all the excuse you need. The film was re-made in 1993 as a more overt comedy, starring Daryl Hannah and directed by Christopher Guest, but the original is funnier.

The Blob (1958) dir. Irvin S Yeaworth jr. A meteorite brings the blob to Earth where it absorbs people and grows in size. Steve McQueen is the plucky teenager who tries to warn the authorities, but is ignored. Rallying the youth of the small American town under threat, he saves the day by freezing the blob until it can be flown to Antarctica. This monster cult-classic spawned a sequel in 1971, Beware! The Blob aka. Son of Blob, directed by Larry Hagman, Dallas's J. R. Ewing. A poor comedy that chewed its way through many guest stars, including Burgess Meredith and Gerrit Graham. The Blob (1988) was an unnecessary remake, lifting whole scenes from the original, but at least it can be said to have been faithful while adding then-state of the art special effects. Directed by Chuck Russell it starred Kevin Dillon (brother of Matt), Shawnee Smith and Donovan Leitch (son of the folk singer), but the original is best.

The Fly (1958) dir. Kurt Neumann. Loosely based on the short story (1957) by George Langelaan. Scientist Al (David) Hedison is experimenting with a matter transporter when a fly enters the machine with him. They become mixed up and he has a huge fly's head and arm/leg. With the help of his wife Patricia Owens he tries to reverse the process, but the fly proves elusive. Eventually wife kills husband by crushing his head and arm in a steam press; the fly is spared becoming a spider's dinner when brother Vincent Price kills it/him with a rock. This version spawned two sequels, Return of the Fly (1959) dir. Edward L Bernds, in which the scientist's son (Brett Halsey) suffers the same fate when a crook (David Frankham) deliberately messes things up. Price, reprising his earlier role, is able to restore him. Then came Curse of the Fly (1965) dir. Don Sharp, in which Brian Donlevy is another scientist from the same family. His matter transportation efforts result in a bunch of deformed people, while his wife, Carole Gray, mentally deteriorates. When Donlevy tries to transport himself to London, his son has destroyed the receiving pod there. The original would be re-made and updated in David Cronenberg's version (see Part Five).

I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958) dir. Gene Fowler jr. This actually followed a film called I Married a Communist and, like a lot of US 50s SF, had its share of reds-under-the-bed paranoia. But it also probably had more than a little to do with wedding-night trauma, bearing in mind that during the 1950s there were far more 'virgin' weddings than nowadays. Be all that as it may, this is a wonderful film in the they-want-to-sleep-with-our-women category. Gloria Talbott thinks her husband is not the man she married, and she s right, Tom Tryon is an alien.! And, yes, they are trying to repopulate their planet, but having little success. In fact the plight of the aliens is handled with sympathy here. Talbott convinces her doctor of what she's discovered and a posse of fathers-to-be is soon rounded up and the aliens defeated. The 1998 remake, dir. Nancy Malone, adds nothing.

It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958) dir. Edward Cahn. Astronauts returning from Mars have a stowaway alien (Ray 'Crash' Corrigan) aboard who wants to feed on their blood. Forced to give up the ship section by section, they eventually don spacesuits and let out the air, asphyxiating the creature. The unlucky astronauts include Marshall Thompson, Kim Spalding, Ann Doran and Shawn Smith. While it can be claimed that Alien (see Part Four) has similarities to this film, both can be said to owe much to A. E. van Vogt's short 'The Black Destroyer' (1939).

The Trollenberg Terror (1958) dir. Quentin Lawrence. This is more or less an adaptation of the 1956-7 TV serial of the same name. On a mountain in Switzerland some mountain climbers are found decapitated as they tried to ascend into the cloud-capped peaks. A girl (Janet Munro) has telepathic powers and she warns that aliens lurk above. As the cloud descends Forrest Tucker and Warren Mitchell stay to help fight the (highly amusing looking) cyclopean, tentacled aliens. Eventually the RAF firebomb the slimy monsters. The cheapness of this film (the 'cloud' is cotton wool stuck to a photograph!) puts this firmly in the so-bad-it is-good category, but it is actually not that bad.

The Brain That Wouldn't Die (1962) dir. Joseph Green. This film was actually completed in 1959 with the working title of The Black Door. However it was not released until 1962 as The Brain That Wouldn't Die. As such it beat Re-Animator (1985) and Frankenhooker (1990) by about two-and-a-half and three decades respectively. This is the story of a mad brain surgeon (Herb Evers) who keeps the head of his fiancée (Virginia Leith) alive after she is decapitated in a car crash. While he looks for a new body for her, she makes contact with the monster (7' 8" Eddie Carmel) he keeps in a closet. When Evers brings back a model (Adele Lamont) to perform the operation, the monster breaks out with the usual consequences. Z-film mayhem.

Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1959) dir. Henry Levin. Based on the Jules Verne novel Voyage au Centre de la Terre (1864) and first filmed under the French title in 1909 by Segundo de Chomon. Starring James Mason and pop star Pat Boone, this is an uneven film adventure with some very nice bits – the underground sea, the field of giant mushrooms, the lost city of Atlantis, etc – and some very bad bits – photo-enlarged iguanas with fins stuck on their backs playing dinosaurs. Arlene Dahl, Diane Baker and Peter Ronson are with the good guys; Thayer David plays the nasty Count Saknussemm, leader of a rival expedition. A remake in 1988 had a Japanese release that year and video release in the US 1989, dir. Rusty Lemorande had Kathy Ireland, comedian Emo Phillips and director (usually) Sam Raimi falling down a hole in a cave in Hawaii and finding Atlantis; and a further remake in 1993 was the pilot for a TV series that was never made – one viewing will explain why (though the 'mole' digger was quite nice).

I hope you can now see what a fertile period the fifties were, though we all have our favourites and stinkers. If I had to choose a couple of fifties 'double bills' for a themed film night, the best would be This Island Earth with Forbidden Planet, but my personal favourite choice would be Fiend Without a Face teamed with I Married a Monster from Outer Space. What that says about me, I have no idea, but the fact remains that most of the films from the fifties are 'good value', so to speak, and are well worth checking out. Even if you watch a few turkeys, there is a good chance you will get a laugh out of them.

To come shortly… Part Three: The Space Age (1960-'69).

This article builds on the previous:-

1: Before the Golden Age (1895-1949).

Tony Chester

Tony Chester was one of the Science Fact & Science Fiction Concatenation's founding co-editors. Though he retired from the editorial team in 2009, he still occasionally contributes the odd piece.

News of current and forthcoming SF, fantasy and related horror films can be found in the 'films' sub-section linked in the index to our seasonal (spring, summer and autumn) sci-fi news page.

See also our listing of current and forthcoming SF/F film releases and our annual box office top ten listings SF/F.

[Up: Article Index | Home Page: Science Fact & Fiction Concatenation | Recent Site Additions]

[Most recent Seasonal Science Fiction News]

[Convention Reviews Index | Top Science Fiction Films | Science Fiction Books]

[Science Fiction Non-Fiction & Popular Science Books]

[Updated: 15.4.15 | Contact | Copyright | Privacy]

|