Using SF/F to justify Putin

The past half-decade Russia's fiction market has seen

a new class of fiction novels, some SF, that portray the

Ukraine as a far-right dictatorial state with

military designs on Russia. Jonathan Cowie

considers an Ukrainian publishers' perspective

We are all well aware of recent events in Ukraine and Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin's purported goal to de-naΖify and de-militarise that country. In Russia itself, Russians today largely get their news through state-run and controlled media: Russian independent media is all but gone and internet connections to western news media and some social media platforms have been blocked. These media controls are recent and so you might well ask why many Russians have bought into the Putin narrative justifying invading Ukraine; after all Russians have had years of accessing other media and news sources. Well, the answer in part is that the Putin era has seen the seeding of this narrative within Russia culture for some years.

First, a flashback. Back in 2006 that year's Eurocon was held in Ukraine: it was Ukraine's first Eurocon and I was there for it. Yet one-and-a-half decades ago back then it was clear that Russia dominated the Ukrainian book market, but there were the embryonic signs that things were getting better with the first green shoots of a new generation of Ukrainian publishing opportunities. But even by 2013, according to the Ukrainian Publishers and Booksellers Association (UPBA), at least 73-75% of Ukraine's total book market were books from Russia: Ukrainian books remained in the minority, accounting for only a quarter. Now, back to the present…

The Ukrainian fan, and SF²Concatenation's ISP facilitator, Borys Sidyuk, recently pointed me in the direction of an article on how Putin's message is promulgated through novels by Chytomo.com a Ukrainian book-market news site. It has to be said that the English in this article is a little clumsy (which is understandable given the translators are not translating into their own language and especially translating in a time of war), hence in part the need for this article.

Since 2009, Russia has been actively publishing books on a fictional, full-blown war between Russia and Ukraine in the fantasy genre, as well as historical and 'non-fiction' books about the 'collapse of the Ukraine project' and mocking the independence of the 'non-existent' Ukrainian people and their 'artificial' Ukrainian language. Remember, the Putin narrative has it that Ukraine is not a real country but a part of Russia, hence Ukrainian is not a real language. It is galling to him that Ukraine's move the past decade or so to a more democratic and western looking nation has seen the country begin to thrive.

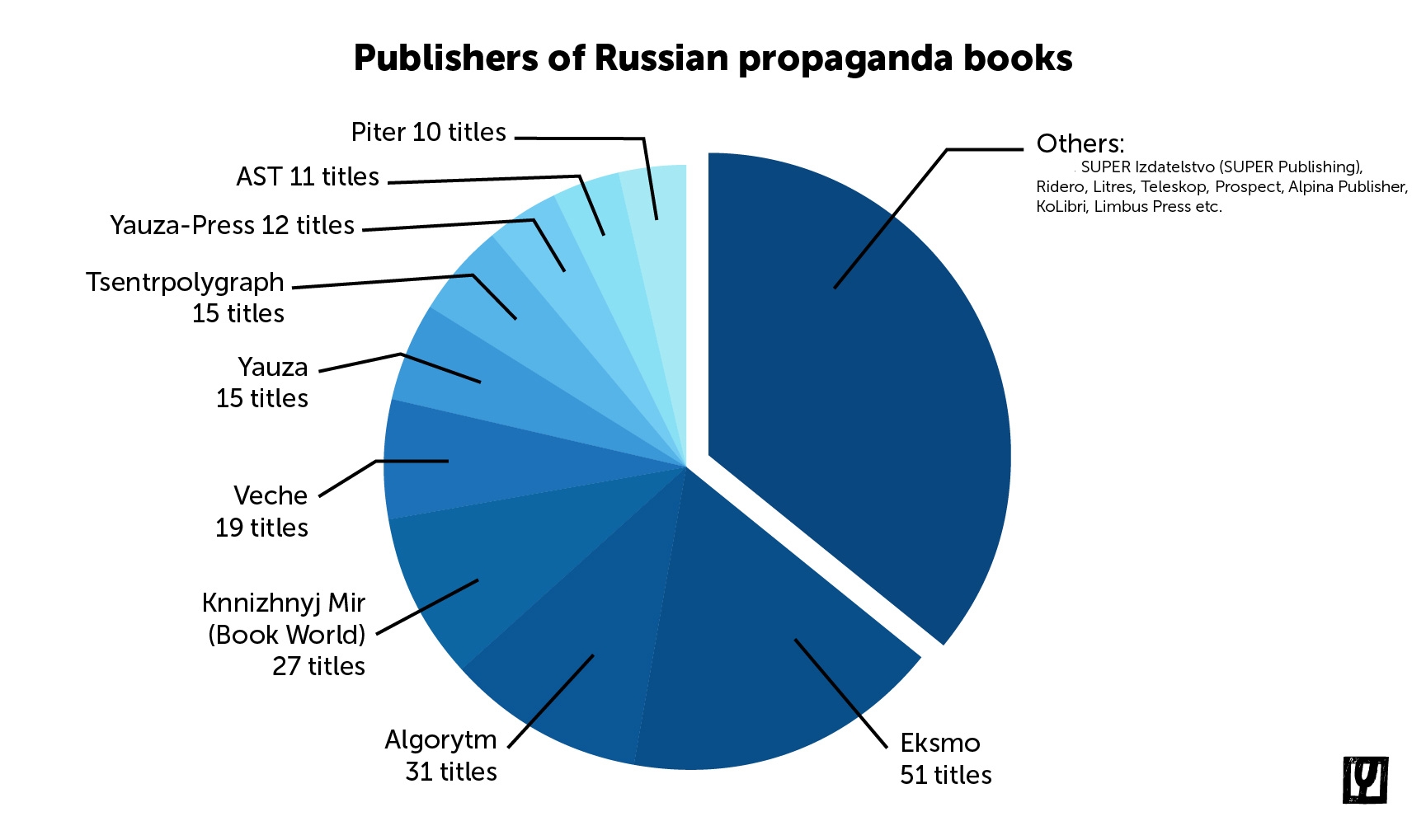

In order to promulgate the Putin narrative, it has in recent years appeared in various guises Russian fiction novels. Naturally, such novels are offensive to Ukrainians and a number have been banned. Chytomo.com provides the breakdown from which you can see that the three leading publishers of such books are: Eksmo, Algoytem, and Knnizhnyj Mir.