Science and Science Fiction

The 2022/3 Science Museum Exhibition

Jonathan Cowie reviews…

No real sub-head; the title says it all.

|

|

|

It is the autumn of 2022 and the Science Museum (Kensington – there are others but Ken is the King) has launched a Science and Science Fiction exhibition called Voyage to the Edge of Imagination. Now, there are a number of SF exhibitions in Brit Cit (and, indeed, Cal Hab and the Emerald Isle) but most are specialist relating to a specific SF franchise or genre format: few are broad based. If memory serves, the last broad one was more literary centric – but did have films and TV genre in the mix – and was held over a decade ago by the British Library (a couple of pictures here). This new one covers SF in many of its forms: literature, cinematic, art, television, comics etc., and its relationship with science.

And there is science too.

For Big Bang Theorists, what's not to like?

|

|

The overall title – Voyage to the Edge of Imagination – was no mere moniker, this was a voyage, a ride, a journey; it had a beginning, a middle and an end. So, do not make the mistake of thinking that this was just a collection of displays with a theme of science fiction and tie-in science: this one has narrative one that at the outset gave visitor an explicit mission. Do not be tempted to rush through; if you do, you will simply miss out.

The departure lounge

The departure loungeTo begin at the beginning, you, the exhibition visitor, or in this case, traveller, embark on your journey, from a departure lounge via a space craft shuttle in which you are greeted by an artificial intelligence who outlines, in the briefest sense, what is going to happen. And on the way in, note the docking number, 1138… Here, many of you will have got it, but for those that did not, 1138 turns up in Star Wars I (the original film – none of this episode x 'New Hope' malarkey). And, of course, this in turn stems from THX 1138 the serious SF film (dystopic, Orwellian and somewhat dark) that George Lucas made before he became famous (and very rich) with Star Wars. Now, I mention this at the beginning because the entire exhibition has a loose sprinkling of SFnal Easter Eggs for the serious, die-hard, and possibly long-in-the-tooth, SF aficionados and fans to discover: no more spoilers, I leave it to you to find them out.

|

Saturn V

Saturn V

The Enterprise

The Enterprise

The First Men in the Moon

The First Men in the Moon

|

Of course, you cannot have an SF exhibition without rockets, robots and ray guns, and if science in the mix then we have got to have the iconic Saturn V in there somewhere. Remember, our rebel colonist friends were the first to take people to the Moon and return them safely to the Earth without the use of Cavorite.

And on the SF 'rocket' front there was almost inevitably Star Trek's Enterprise

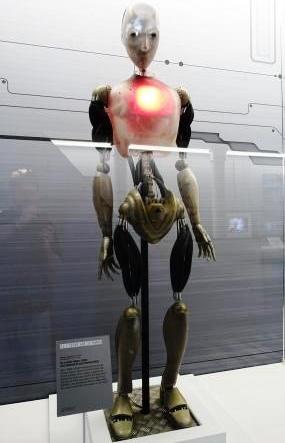

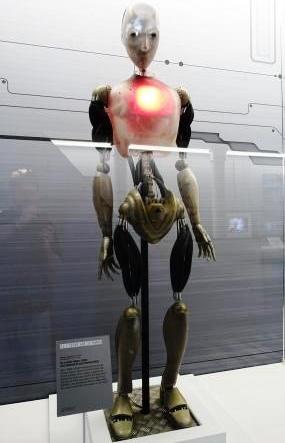

With regards to SF robots, in the mix were: the 'Maria' robot made for Fritz Lang's film Metropolis (1927); Gort from The Day the Earth Stood Still; and the robot from the film I Robot. All good stuff

As for the ray guns? Well, these were in short supply, but there was a tricorder from Star Trek along with a real-life diagnostics display.

There were real robots there too including one made by Toyota that did not look like a robot but was, in fact, the real deal.

Though not a robot, more a cyborg, there was also a second Dalek in the exhibition (in addition to one outside in the foyer). However this one had been slightly damaged as it was lacking its speech lights' coverings revealing small, good old-fashioned thermo-electric light bulbs underneath: clearly the Daleks were not that advanced, no LEDs.

Speaking of travelling to the Moon without Cavorite, there were early edition copies of Jules Verne's From the Earth to the Moon (1865) and H. G. Wells' The First Men in the Moon (1901). These turned out to be illustrated and the exhibitors thoughtfully held them open without breaking the spine at one of the illustrations. The latter one depicted the weightless nature of space travel portrayed in the novel and half a century before any human actually experienced it for real.

|

Maria from Metropolis.

Maria from Metropolis.

© Science Museum Group (2022)

|

Gort

Gort

The Day the Earth Stood Still

|

A robot from I-Robot

A robot from I-Robot

|

Toyota robot. © Science Museum 2022.

Toyota robot. © Science Museum 2022.

Doing the Drake equation.

Doing the Drake equation.

Part of SF and real

Part of SF and real

artificial intelligence display

Part of SF with an

Part of SF with an

environmental theme section

|

Yet, here's the thing, in what Carl Sagan called 'science and science fiction's dance', the lines are blurred. Some of today's science fiction will truly become part of tomorrow's science fact. This has already happened a number of times. Advanced computers with a seeming mind of their own have been a standard SF trope since the 1950s and Isaac Asimov did not invent the concept of intelligent robots in the 1940s but popularised it.

Indeed, some areas of science seem more-rooted in science fiction than fact. One of these is contemplating whether there are other technological alien civilisations in the Galaxy. Here, the recently late, Frank Drake's eponymous equation is almost iconic.

N = R* fp ne fl fi fc L

N = the number of technological species in the Galaxy.

R* = rate of star formation per year

fp = the estimated proportion of stars with planets

ne = the estimated proportion of planets capable of supporting life

fl = the estimated proportion of life capable planets actually having life

fi = the estimated proportion of living planets having intelligent life

fc = the estimated proportion of intelligent species developing communications technology

L = the lifetime of the average technological civilisations in years.

The exhibition gave visitors the chance to make and input their own estimates and then made the calculation.

I have to say that here I think the exhibition's curators missed a trick. First, once the calculation was made, it would have been trivial for them to add the average distance to the nearest one. Second, we already have a good handle on a number of these estimates. In fact, only fi, fc and L are subject to any major debate. The display might have noted which elements science has ascertained (such as the proportion of stars with planets through recent space telescopes and wobble as well as occultation astronomy) and then focused on those elements that were truly uncertain (Drake himself came to the conclusion that N = L. For if an intelligence having developed radio astronomy then went on to, say, have a devastating nuclear war then L might be small. Conversely, if an intelligence used technology to make their planetary society sustainable and secure from existential threats, the L might be very large.

|

Uhura's uniform in

Uhura's uniform in

Star Trek: The Motion Picture

|

Among much else, science fiction is inspirational not only sparking the imagination but helping engender an interest in science and even science as a career choice (something we have touched on before including back in our print days – archived here) The actress Nichelle Nichols is famous for having played communications officer Lieutenant Uhura in Star Trek but was thinking of leaving the show after the first season for fear of being typecast. However, famously the civil rights activist, Martin Luther King encouraged her to stay as she was a role model for African American women. This she did and the rest, as they say, is history.

One of those she inspired was Mae Jemison who went on to become an astronaut who had a mission on the International Space Station (ISS). Nichelle Nichols sowed the seed in Mae Jemison's mind that perhaps being an astronaut could be for people like her. Both Uhura's uniform from Star Trek: The Motion Picture and a picture of Mae Jemison in the ISS were on display.

|

|

Mae Jemison, International Space Station astronaut.

Mae Jemison, International Space Station astronaut.And here's the thing, and one which the exhibition did develop as one of its themes. It noted that we humans are warlike and living in a non-sustainable way with our planet. There were SFnal comics and displays firmly making this point including the cover art for Kim Stanley Robinson's New York 2140 which portrayed that city in a globally warmed world. There was also the short film Pumizi (2006) about a woman curating a habitat who plants a plant in the arid desert… (I have to say I did not take to this film at all. The – as subtle as a miners' outing – message being we need to nurture nature was fine but alas was delivered with little nuance. And then at the film's end, as we pan back we see that some miles away there was a verdant area in which the plant would have flourished… The film was an artistic triumph of style over substance.) Nonetheless, there was plenty of other good stuff to see.

|

© Science Museum (2022)

© Science Museum (2022)

|

The exhibition had its heart firmly in the right place and made it clear that SF, among much else, includes environmental conservation and sustainability stories.

As visitors were leaving, the final display was a view of Earth from space as if one was in an orbiting space station. We were given a concluding message from the exhibition's pseudo-artificial intelligence that we humans were both destructive and creative. Here the stories we tell, the science fiction we create can serve to warn as well as encourage solutions. What we do is up to us…!

So, all in all, despite feeling a little muddled and sort of thrown together, this was a very positive exhibition with a very worthy, take-home message.

Left: A metal urn that survived the Hiroshima nuclear blast. Humanity has a destructive side.

|

|

|

Problems, only a few. A fundamental issue is the lack of clarity in the voice of the artificial intelligence guide which I suspect might get drowned in the hubbub of a crowd (it was fairly quiet during our visit). One issue is that the exhibition seems a little disjointed and thrown together, but maybe that is me?

Of course, every seasoned SF fan could list things that they feel should have been included but the creators only had a finite space and so it would be churlish to dwell on this. Nonetheless, it being the year 2022, I did wonder if the book Make Room, Make Room and its cinematic adaptation Soylent Green should have been in the mix? The film itself was set in 2022 and the first edition of the book had an environmental reading list as an appendix. One thing that certainly did not work – as was echoed by my accompanying SF² Concatenation colleague Tony – was the space-time 'wormhole' room that connected two sections of the exhibition. It really was not much with little to see and, to be honest, it was a bit of a waste of space: personally I would have had, say, a surrounding high-definition Martian panorama taken by one of the rovers, and red sand with some rocks either side of the walkway to simulate the Martian surface. But this really was the only major let down. The one thing I did notice at the exhibition's end with a display of those who had contributed to its curation was the paucity of SF authors who were scientists. Why did not the museum tap them for ideas at the outset? Had they, the exhibition could perhaps have been even better!

Finally, we come to the question as to whom the exhibition is aimed? The die-hard, seasoned SF aficionado and sercon fans will at least be curious as to what is included even if they learn little new (some may even be disappointed). It is perhaps the occasional consumer of SF that will gain the most. Who certainly may be inspired are youngsters, possibly young teenagers. This then is a family exhibition: parents might be reminded of SF offerings that they enjoyed in the past, while youngsters will get a taste of sense-of-wonder and perhaps learn of SF works they may wish to check out, as well as to look at their science classes in a new light.

Perhaps the best thing about this exhibition is that it is happening at all. I remember all too well in the latter half of the 20th century that science fiction was, by many, regarded as frivolous if not downright infantile. Certainly, embarking on by own career in science, being something of an SF fan was not something one talked about with one's professional peers. However, over the decades matters have gradually changed. The entertainment sector has realised that SF means big business. Just look at the weekly cinematic box office ratings and genre films regularly make up around a third of the top twenty. Genre book fiction in Britain has held steady across the decades making up between around 8% and 12% of mass-market sales: the range is more to do with how one defines SF/F. What certainly has happened is that the standard of genre best-sellers has improved: Asimov today – as much as I enjoyed his fiction as a youngster – certainly seems dated and his characters shallow (as well as at times sadly seχist). SF is now giving mainstream mundane fiction a run for its money just this week one of Britain's most prestigious fiction prize, the Booker, has gone to a fantasy horror novel. SF has come out into the light. Indeed, we live in what was an SFnal world with the internet, personal communication devices cum cameras, cum electronic wallets even if smart phones use environmentally damaging rare earth elements and the energy needed to power the internet and mobile (cell) communications network has a carbon footprint of a similar magnitude as the air sector. Today, virtually every home has a computer even if not all dwellings (in developed nations like Britain) are on the internet. The lines between science, technology, science fiction and our very lives have become blurred. It is therefore not that surprising that we now have a major SF exhibition at one of the nation's principal museums. Do support it if you can by going to it, and if you have a young family then give them a treat. It might be quite a while before we, in London, get another with such scope.

At a pinch, you can do the exhibition in over an hour, but if you did that you would not be able to read everything at all the displays and for sure you would miss out on some Easter eggs. So do budget for well over two hours and take your time. Finally, if you want more then on the way out there was an SF gift shop which included a companion book to the exhibition.

With that, just tread boldly Kensington way.

Jonathan Cowie

Pictures by Tony Bailey unless otherwise credited to the Science Museum for which thanks goes to its press office.

|

|

|

Jonathan Cowie is an environmental scientist who has had a career in science communication (publishing, policy analysis and advice to Parliamentarians and Government Departments and their agencies). Who has in the early 2000s specialised in climate change biology but the past few years has developed his interests in Earth system science across deep time: the co-evolution of life and planet. He is also one of SF² Concatenation's founding editors.

|

|

|